What I have in common with Sigismondo Polcastro (1384-1473)

I found an absolutely remarkable thing on the internet a few weeks ago. Academic Tree is a site dedicated to “building a single, interdisciplinary academic genealogy.” Here's the premise: every professor who mentors graduate students was once a student researching with a professor. In turn, this professor must have once researched under another professor, et cetera, et cetera. This creates a lineage of researchers that can be traced back for hundreds of years of scholarship and research. So, Academic Tree is a website that hosts academic family trees- and provides an important perspective.

As graduate students, the TPS fellows and myself are in different stages of creating research programs under the guidance of a mentor. These consist of experiments conducted to answer some set of fundamental, unanswered questions. For me, researching molecular plant science, these are questions like “What is the role of water in the beginning of bacterial diseases?” Based on what a student's experiences, the questions driving their research may change from those of their mentor. Through consideration and encouragement, the student develops a new research program that strives to answer research questions of their own- often with some overlap of their advisor’s research. With this in mind, what will be the effect of this person-to-person shift over 20+ generations? How much do research interests change over the course of centuries? In Academic Tree, I found a resource that allowed me to consider that question. So, I decided to research my academic history as far back as I could go, and report the results here.

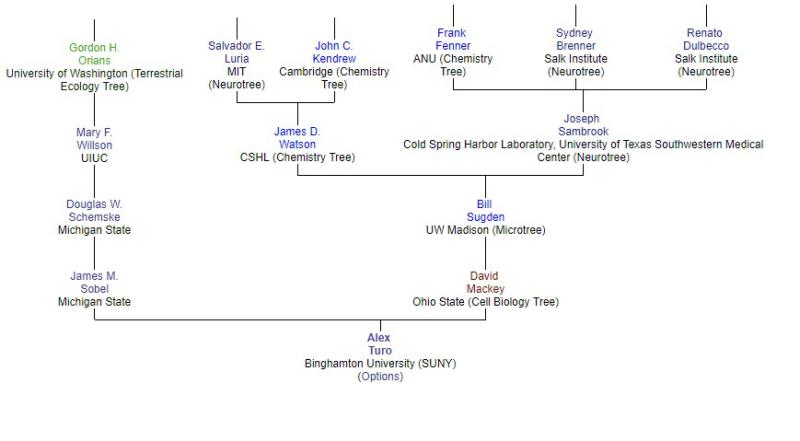

First, there’s me, Alex Turo. As you can see in the figure, I have two mentors on Academic Tree. That's because before beginning my doctoral studies at tOSU, I studied with James Sobel at the State University of New York. Here, I’m only going to focus on my lineage through Ohio State. Sorry Jay!

So, I already knew my mentor, David Mackey, completed his doctorate at the University of Wisconsin with a virologist named Bill Sugden. However, I didn’t know before now that Sugden had completed his doctorate at Columbia where he had two mentors: Joseph Sambrook and James Watson. Sambrook is one of those names that people who spend all their time in a genetics lab knows. He is the author of “Molecular Cloning,” a titanic, three-volume manual that is like the bible of molecular genetics. Watson, though, is still a borderline household name when used in the context “Watson and Crick” (i.e. Franklin et al). The man was part of the team that resolved the structure of DNA’s double helix.

Let’s continue this adventure on Watson’s path. Watson worked with Nobel laureate Salvador Luria, a microbiologist at the University of Indiana and later MIT. From there the trail crosses the Atlantic; Luria worked with Giuseppe Levi at the University of Torino in Italy. He graduated with his doctorate in 1935. By the mid-19th century, the lineage has moved to Germany and bounced around universities there. That is, until Johan Meckel moved from Paris after completing his PhD in 1805 when he studied with Georges Cuvier (Wikipedia). Cuvier was an exciting find for me as well; he is referred to as the “founding father of paleontology.” The next 11 generations pass in Western European universities until Theodor Zwinger, ardent defender of the alchemist Paracelsus (oh boy), emigrates from Italy after receiving his doctorate in 1559. Another researcher of note in the lineage during this period is Gabriele Falloppio, who in a bold move named fallopian tubes after himself. The trail finally ends goes dead after another five generations at Sigismondo Polcastro. Polcastro was, by my Googling, something of an early pharmacologist born near Venice in the 14th century. Whoever trained him, though, is something lost to history.

And there it is. A lineage connects my research to research conducted in Italy less than a half-century after the Black Death decimated Europe. What’s the point of any of this? In my view, the twenty-five generations of scientists preceding myself form a lineage of people who improved the human experience through better understanding of the physical world. In fact, the majority of these people were dedicated to understanding health and disease. As a researcher who studies the molecular basis of disease in plants, I realize I haven’t lost the path. The goals that drive my research are little changed from any of my academic forebears who lived more than 500 years ago. Polcastro and I both struggle to understand the role of bacteria in disease. I just have the advantage of microscopes and DNA sequencing. So what does it matter that my mentor moved from human viruses to plant bacteria? Or if my great-great-great-great grand mentor moved to amphibian cell biology from micro-ophthalmology? We're united in our goal to understand the physical world in a way that improves our quality of life. So, an hour spent exploring Academic Tree might be a good investment for all researchers to find a sense of perspective. What are the questions guiding our research in 2018 that connect us to the scientists who came before us? Which ideals and visions might we share? Which questions will outlive us?

Written by TPS Fellow Alex Turo