Discussing Climate Change and Agriculture

I was recently invited to address a public meeting of the Sierra Club, an environmental activism organization, in Columbus, OH to discuss the projected effects of climate change on agriculture. It was an opportunity that I was eager to seize, as scientific outreach has been a priority for me since before I was an undergrad, and since neither climate change nor agriculture are foreign subjects for the Sierra Club, I was looking forward to hearing what the greater public in attendance would have to say. For that reason, I designed a presentation that I hoped would invite questions and well-intentioned skepticism, and also discussed both global features of climate change and also effects that are specific to our region and state.

In particular, I was interested in beginning with an overview of agricultural systems at global, national, and regional levels, because I wanted to communicate the massive scale of these systems. Consider, for example, that approximately half of the global workforce (i.e. 1.5 billion people) depend on agriculture for income and employment. This accounts for ~70% of the world's rural poor, who are incidentally among the most at-risk human populations to suffer the negative impacts of anthropogenic climate change. Closer to home, far fewer people in the U.S. rely on agriculture for employment; <1%- 4% of jobs in America are agricultural depending on how you want to count. This number is higher in Ohio, though, where the Ohio Farm Bureau reports approximately 1/7 jobs in the Buckeye state are related to agriculture.

With these numbers in mind, my preparations for this talk brought me in contact with the idea of "adaptive capacity" with regards to climate change's pressure on food security. A cornerstone of climate policy, it means exactly what it sounds like it does (i.e. the ability to effectively respond to new problems), it gives us a helpful framework for thinking about how we should prepare to mitigate the effects of climate change. For example, one of the immediate concerns in climate change's impact on global agriculture is the disruption of regional food security. We don't need to look any further than the ongoing Syrian crisis to see why threats to food security challenge the interconnectedness of environment, economics, and socio-politics deserves our study and attention. This is one of the reasons that the buzzword "resilience" gets thrown around along with "sustainable" when we talk about our food system; failure to build a resilient food system could mean that when a spark of unrest lands in dry straw, instead of losing the loft we lose the whole farm.

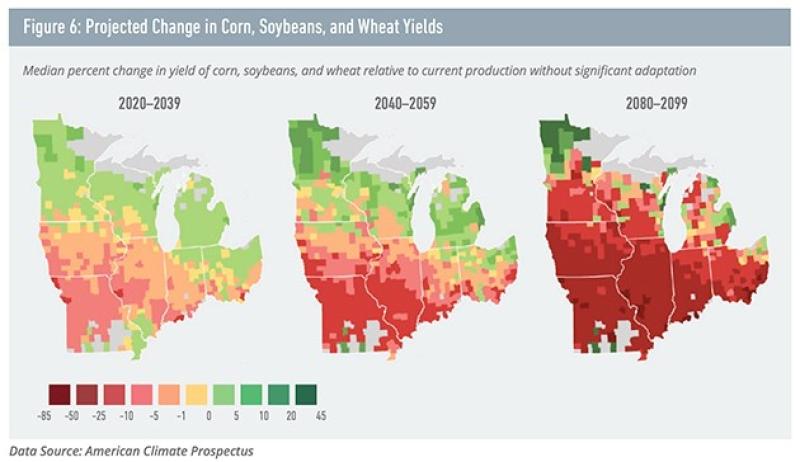

Therefore, I think that to maintain a stable food system, there are three categories of action needed to keep our system healthy and resilient: firstly, we need to research climate change; it surprised me to see how (relatively) scant the literature is in terms of projecting the effects of changing climates on agriculture. What literature there is, is excellent (e.g. the Risky Business Project, figure 6 included below), and doubtless there is going to be a thunderous emergence of published research on the subject in the near future, but since the first step to evading a trap is knowing that it's there , the research cannot be published soon enough. Secondly, we need to innovate our farming methods and put the pedal to the metal on crop and livestock breeding efforts. The role of biotechnology cannot be over-emphasized in this area; Sub-Sahara is projected to grow substantially more arid over the next 50 years, and drought-resistant GM crops are set to nourish a Borlaugian number of lives in the region. Finally, we need to enact climate-smart agricultural policies to afford our farms the resilience they need to thrive in the long-term. I think it's vital to take the onus off of farmers to shoulder the financial burden of adapting to different climates; the American Farm Bureau does not oppose climate change legislation out of spite. The Farm Bureau knows that for every three acres an American farmer plants, one of those acres is bound for export. So, if carbon taxes raise the price of exporting apples to SE Asia, then it's ultimately the farmer losing money, and that should be acknowledged. Now, I am not lobbying for or against the pro-export bend of the American agricultural system; I only know that most people act in their own self-interest when running low on money, social capital, and "adaptive capacity."

And that is where I left the Sierra Club meeting that day. I was glad to have the opportunity to help others think about how our changing world will affect agriculture in India, Kenya, and Brazil- and also the Scioto River Watershed. I learned a lot from the variety of perspectives in the room that evening, and I hope to attend more community events with the group in the coming months- both at the podium, and also in the audience.

Written by TPS Fellow, Alex Turo